Optimixace označuje praxi výběru a kombinování prvků z různých metod v naději, že výsledná kombinace povede k vyšší úrovní kvality řízení. Analogie: Jak pejsek a kočička vařily dort. I když se to může jevit jako racionální strategie, často pramení z ritualizovaného a neohraničeného procesu trvalého inkrementálního zlepšování – i když situace vyžaduje hlubší reflexi nebo […]

Blog

Meetup CIO25

Úspěšně proběhl další ročník neformálního setkání CIO na téma ´Dopady AI na IT management´. Na meetupu zazněly tyto příspěvky: Zdeněk Kvapil, Q4IT, „Dopady AI a digitálních agentů na IT management“ Pavel Janko, Moravio CTO + Jakub Bílý, Moravio Head of Business, „Ready Your Company for an Uncertain AI Future – Data & APIs Before UI“ […]

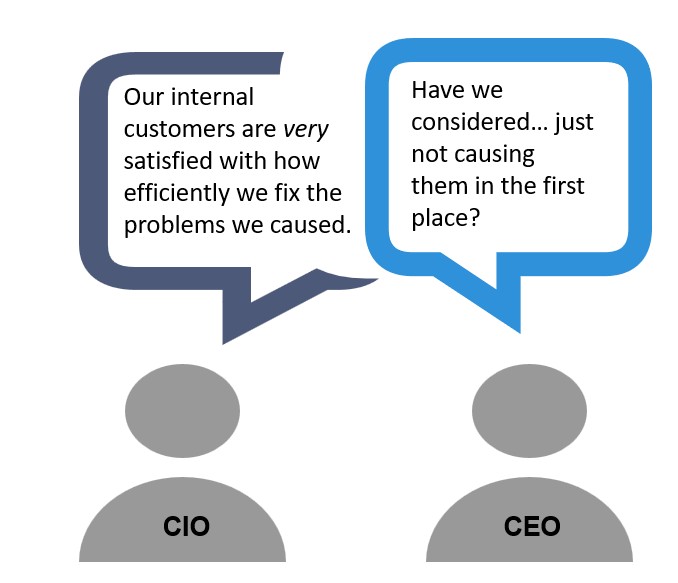

Continually Improving the Wrong Thing

…such as the customer experience of fixing broken IT systems. The service industry evolved long ago, around the time when innovative services began targeting top-tier clients willing to pay premium prices—think airlines, banking, and hotels. In those sectors, delighting customers by delivering an outstanding experience was a legitimate strategy: it helped grow the market, improve […]

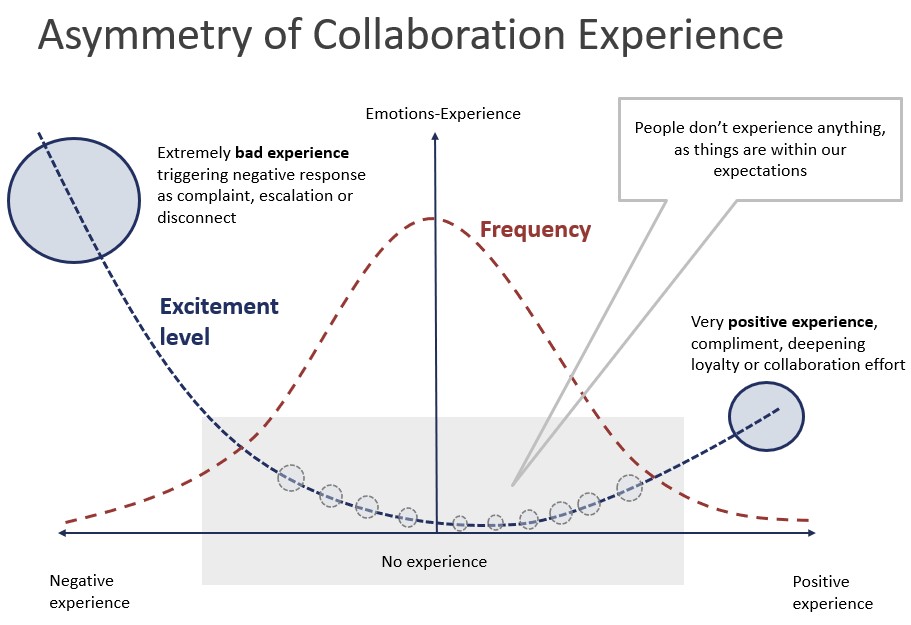

Zpětná vazba – víc škody než užitku

Zvyk sbírat zpětnou vazbu po každé interakci se stal rozšířenou špatnou praxí – poháněnou nekritickým přebíráním zákaznicky orientovaných modelů řízení do oblastí, pro které nebyly původně určeny. Slogany jako „Zákazník je král“ nebo „Jsme tu pro vás“ odrážejí myšlenkové vzorce, které jsou uplatňovány v kontextech, jež se zásadně liší od transakčních vztahů, pro které byly […]

The 12 Outdated Assumptions Still Used in IT Management

Colleagues Prefer to Be Treated as Customers Collaboration is often mistaken for a service relationship. Unlike transactions, collaboration is non-transactional and requires a fundamentally different approach. Demand Is Endless The belief that working faster and more efficiently will meet endless demand overlooks what truly matters: delivering meaningful outcomes. Quality and relevance outweigh speed and volume. […]